1. Introduction.

One curse, said to be of Chinese origin, made a stunning career over the last decade. “May you live in interesting times [1]”. Indeed, such times are unarguably upon us. Closed businesses, empty streets, citizens waiting in their homes for the silent storm to end. Staying within your four walls is especially crucial in order to implement the most effective method of combating pandemic – social distancing [2]. However, a safe shelter is an integral part of being able to practice it successful. What for many Europeans may seem rather obvious, is an impassable obstacle for thousands of asylum-seekers, in search for international protection. While difficult for us, Covid-19 pandemics could be devastating for displaced persons and refugees [3].

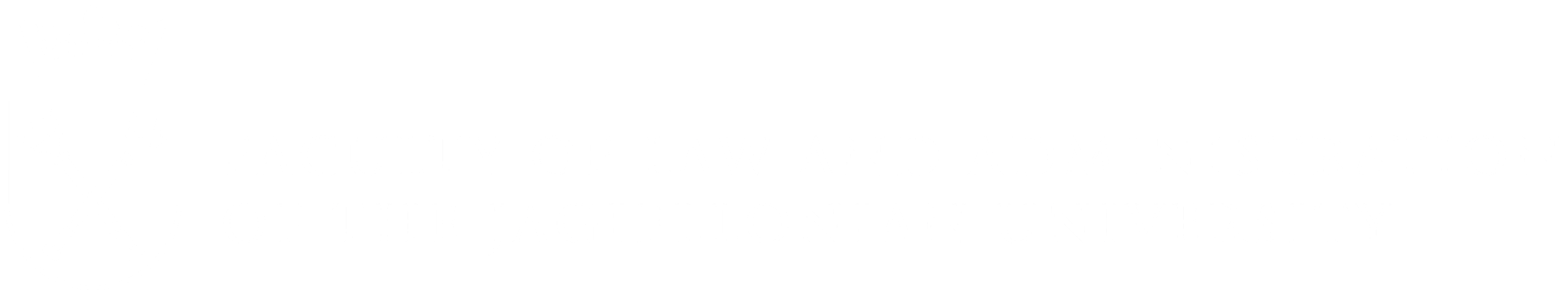

Most recent data gathered by UNHCR as of March 2020 indicates lower number of persons trying to reach Europe than in March 2019 (picture 1). We are yet to observe the way the pandemic will influence global migration flows. On the one hand, there is a chance that such diminishing trend will continue, as the situation in Europe may prevent potential migrants from crossing Mediterranean Sea. On the other hand, once SARS-CoV-2 reaches southern countries, especially those damaged by internal conflicts like Syria or South Sudan, where state agents are too vulnerable to tackle the threat swiftly, citizens of those countries may try to seek safety in northern countries. Chief of the African Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (ACDC) called Covid-19 “an existential threat to (our) continent”, especially due to a lack of ventilators, crucial in combating the virus [4]. With such prognosis in mind, Europe should prepare for surge of immigrants at its gates.

Picture 1: Statistics of immigrants’ arrivals across Mediterranean Sea; source: data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean.

I believe that such preparation can, and must, be created in the spirit of solidarity [5] and founded on the basis of binding international law. European approach to tackle the upcoming crisis should prioritize vulnerable groups – refugees, displaced persons and migrants. In my article I wish to enumerate several issues connected with granting international protection that are relevant to the current unprecedented crisis.

Legal framework of international protection in Europe is built on three levels, all of which have to be kept in mind while discussing the matter of possible “Covid-migrants” in Europe. Firstly, international acts, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Geneva Convention relating to the status of refugees. Secondly, European Convention of Human Rights should be remembered- especially its article 3, interpreted numerous times by the European Court of Human Rights in terms of international protection. Lastly, what is relevant for the European Union Member States, European Union Law, particularly EU Treaties and Qualification Directive, as interpreted by the Court of Justice of the EU.

2. International State of Emergency: key to flexible management of migration flows.

Before we even begin discussing provisions of International Refugee Law, one may doubt whether it is even useful. Current situation is disastrous, assets are limited and citizens should be given priority. Also, mass influx of persons into Europe can worsen the pandemic, both by bringing the virus back in a mutated form and by giving the virus a new habitat to settle in. Such claims were already stated explicitly by Hungary’s Prime Minister [6]. This approach, as long as it is free from hatred, and rooted in binding international law, may be considered justifiable. In other words, international law allows, under certain circumstances, to temporarily modify its protective norms in situations of emergency. My goal in this section is to enumerate several pieces of legislation on that topic, explain how they function, and apply those provisions to a hypothetical surge of immigrants in connection with Covid-19 pandemic.

For centuries norms regulating state’s responsibility for wrongful acts were virtually non-existent. However, regulations on that matter were created gradually in customary law, widely accepted as equal to conventions [7] Owing to the efforts of International Law Commission, customary law provisions were gathered in one text in order to create the basis of future written convention. While it is an ongoing process, Articles on Responsibility of the State for Internationally Wrongful Acts are often cited by lawyers, courts and tribunals [8] as a basic source of explanation, how state responsibility functions. And not only that – these Articles include provisions regulating when state’s responsibility is limited: situations of force majeure, distress and necessity [9]. Especially the first one is relevant from the point of view of Covid-19 Pandemic. Force majeure is defined by the Articles as “an occurrence of an irresistible force or of an unforeseen event, beyond the control of the State, making it materially impossible in the circumstances to perform the obligation” [10]. It is rather safe to admit that rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 can be described as “irresistible force beyond the control of the State” [11]. This implies that the breach of international law can be justified, if the wrongful action is an effect of such irresistible force [12]. Similar mechanism exists also in International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, updated with non-discriminatory clause [13]. For European nations most relevant and precise provisions are written in European Convention of Human Rights. In normal state of affairs, those rights are linked with limitation clauses, which are certain rules on how to legally restrict use of a certain right (sometimes included literally in the text of Convention, sometimes interpreted by the European Court of Human Rights). However, in the time of war or emergency threatening nation’s life, government may exercise a derogation clause [14]. After notification to Secretary General of Council of Europe, public authorities are able to take measures which usually would be considered as contrary to the obligations established by the Convention. Several states, like Latvia and Romania, already triggered that mechanism successfully. Putting all of those provisions together allows us to conclude that, in case of hypothetical mass influx of persons due to Covid-19 pandemic, some provisions of international law may be limited – owing to state of emergency or force majeure. Thus justifying actions, which in normal state of affairs would be considered wrongful, giving the state increased flexibility to deal with the novel coronavirus.

Nevertheless, limited responsibility does not imply “suspending norms of international law” [15]. Every single of those clauses still puts some boundaries on state agents. For instance, according to the aforementioned Articles, the justification of force majeure does not apply, after the State assumed the risk [16]. More specified rules (and more applicable in the case of European states) are given in ECHR – even if derogation mechanism is triggered correctly, article 15 does not suspend the responsibility for breaching article 2 (right to life), article 3 (prohibition of torture, degrading or inhuman treatment), article 4 paragraph 1 (prohibition of slavery) and article 7 (nullum crimen sine lege rule) [17]. Moreover, exceptions from rules created by the Convention should always be as far-reaching, as the emergency requires. The idea behind such regulations is simple: while certain extreme situation may call for swift measures, public authorities have to maintain certain standards, which are unanimously considered fundamental.

What does that mean for possible mass migration in connection to SARS-CoV-2 pandemic? Two major implications. One the one hand, states cannot close their borders for potential asylum seekers – owing to principle of non-refoulement. This binding norm of international law prohibits the states from expelling in any way asylum-seekers, if such expulsion would result in their death, inhuman or degrading treatment. European Court of Human Rights connected that principle with article 2 and 3 of the Convention, so even if mechanism of derogation is successfully triggered, immigrants still will be able to claim their right to apply for international protection – at least for time needed to clarify whether there is a credible threat to the individual’s life.

At the same time, European states have a variety of options limiting asylum seekers rights, owing to necessary steps to combat Covid-19. After examining the ECHR carefully, one may notice that mechanism of derogation allows governments to limit, for instance, right to fair trial (article 6), right to privacy and family life (article 8), freedom of expression (article 10), and even suspends the prohibition of compulsory labour (article 4 paragraph 2). How can this be used in practice? States may, for instance, prolong or quicken their asylum procedures (for the sake of the right to free trial), or accommodate asylum seekers in stricter, less comfortable conditions, especially during first fortnight, in order to find potential bearers of Covid-19. In general, as long as the steps taken are strictly required in fighting pandemic, governments have a variety of options to loosen their obligations to asylum seekers. The most crucial value in that process is maintaining the balance, between epidemiologic needs and basic rights of the asylum seekers- especially those rights that stem from the principle of non-refoulement.

3. International protection claims based on Covid-19 pandemic – “Covid-migrants?”.

While the first section of my article was rather non-controversial, second part covers the topic that may spark some fierce public debate in the future. One cannot exclude the possibility of immigrants seeking international protection on the ground of Covid-19 pandemic in their country of origin. Even if such idea may seem absurd at first glance, in Europe cases were already settled on similar matter. Does that imply that hypothetical “Covid-migrants” may potentially seek asylum?

In European Union, basic instruments of international protection are enumerated in the Qualification Directive- a legislation rooted in the 1951 Geneva Convention . According to this Directive, a refugee status is granted to a person who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group, is outside the country of nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of that country, or a stateless person, who, being outside of the country of former habitual residence for the same reasons as mentioned above, is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to return to it” [18]. Because those conditions are quite restrictive, the Directive, also includes an institution called “subsidiary protection”. It can be obtained by an individual who did not meet the previous criteria, but upon expulsion to his or her country of origin “would face a real risk of suffering serious harm as defined in Article 15” [19]. Those conditions do not explicitly state the right to asylum owing to pandemic or other health-based reason and thus, in order to understand potential applicability of refugee status and subsidiary protection for Covid-migrants, one has to turn to judicial verdicts on that matter.

Official interpretation of the EU secondary law is performed by the Court of Justice of the EU. Most relevant judgment for the research question of this article was given in the M’Bodj case in 2014. The claimant intended to obtain either refugee status or subsidiary protection on the basis of his AIDS illness and impossibility to continue his treatment upon expulsion. While it could have been viewed from different nuanced perspectives, as it will be discussed below, the CJEU chose a rather strict approach. “Article 15(b) of Directive 2004/83 must be interpreted as meaning that serious harm, as defined by the directive, does not cover a situation in which inhuman or degrading treatment, such as that referred to by the legislation at issue in the main proceedings, to which an applicant suffering from a serious illness may be subjected if returned to his country of origin, is the result of the fact that appropriate treatment is not available in that country, unless such an applicant is intentionally deprived of health” [20].

Following that judgment one can observe that when a state-agent, by an action or omission, deliberately puts a person in danger of suffering from Covid-19 infection, such victim should be able to receive some form of protection – either subsidiary, as due to credible threat of death or inhuman treatment, or even a refugee status, after meeting other conditions from the Directive (most relevant in our case would be those concerning the grounds of persecution). How this kind of state-led actions may look like? For instance, intentionally limiting the access to drinking water, and thus preventing people from taking necessary hygienic means of protection against the virus. This is specifically what Turkey is accused of doing in Northwest Syria [21], not a theoretical situation. Another interesting source of possible asylum claims may be a deliberate policy when, instead of social distancing, government decides to allow the virus to spread (and people to suffer), for the sake of herd immunity and economic reasons. Approach of Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro may serve as an example [22]. Nonetheless, discussion on that question exceeds scope of this article and requires broad medical research.

However important the M’Bodj case was, it did not expand the ground of granting international protection in the EU law. Pandemic-related incidents are just a variation of acts of persecution mentioned in the refugee definition. That being said, the non-refoulement principle is not precluded to EU instruments, and in certain cases may put obligations on the public authorities to abstain from removal of an individual – also, when a threat of death, inhuman or degrading treatment upon removal is not caused by an intentional act of the state. In order however to describe those obligations, one must move from Luxembourg to Strasbourg Court.

Whether a person has a right to asylum based on the lack of proper healthcare was the basis of several cases before European Court of Human Rights [23]. At the beginning the N v the United Kingdom judgement should be examined.

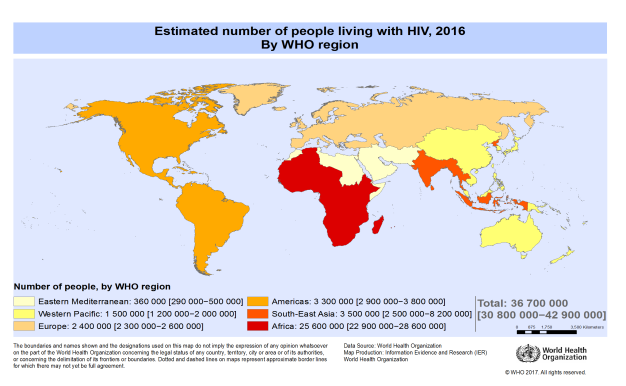

Applicant in that case arrived to the UK seriously ill and was immediately transferred to the hospital, where she was diagnosed as HIV-positive. With several other conditions (Kaposi’s sarcoma and tuberculosis), she required HAART therapy – which, in order to be effective, needed constant visits to the hospital, so that ingredients and dosage of the medicine could be precisely chosen. While in the UK such treatment was possible, in Uganda only half of patients in need could receive it [24]. As Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead said, upon Applicant’s arrival at Uganda, “her position will be similar to having a life-support machine turned off” [25]. Which was as relevant then, as it is today, HIV/AIDS remains an undefeated global health concern, with every 1 in 25 adults in Africa infected with that virus (as shown in Picture 2). Applicant lodged an application to obtain refugee status upon ill-treatment by the National Resistance Movement in Uganda, which was denied by the UK. Then she tried to stop her removal on the grounds of her health state and thus the case was referred to the court in Strasbourg.

Picture 2: scale of HIV/AIDS pandemic in 2016, data gathered by WHO; source: gamapserver.who.int/mapLibrary/app/searchResults.aspx.

Judges in ECHR were reviewing Applicant’s expulsion to Uganda as a potential breach of article 3 of the European Convention of Human Rights, so as a breach of non-refoulement principle. At first, they implied a difference in reviewed case from “typical” claim based on article 3: while usually the potential danger to the asylum-seeker origins in intentional act or omission of state-agent or from non-State bodies when the authorities are unable to afford the applicant appropriate protection, threat to N.’s life lied in unintentional lack of resources due to her country’s poverty [26]. Secondly, it specified the rules set in D. vs the United Kingdom judgement – an earlier verdict where the expulsion HIV-positive patient was stopped. According to the ECHR, receiving asylum on the grounds of lack of required health treatment in country of expulsion was possible only under exceptional, compelling humanitarian grounds [27]. Such conditions were not met by the Applicant, as she was fit to travel, had family in Uganda and had a chance of acquiring therapy in her country of origin. Only imminent death was chosen as a reason to grant an individual some kind of stay permit. One could say that Court chose this high threshold, because international protection as an institution stems from obligation to respond to human-made evil, not any kind of evil. Subsequently, judges justified their decision by referring to the balance between common good and individual rights. Lastly, the test of “compelling humanitarian grounds” from this case was chosen as a standard one in every future case concerning the expulsion to a country of origin a seriously ill person [28]. What is also worth mentioning, any judgment of ECHR does not prevent the state from ranting different type of stay. That judgment was heavily criticized for being too restrictive in its nature [29] and difficult to execute in practice.

After several years, another case was brought before Strasbourg Court, known as Paposhvili vs. Belgium. This time, the Claimant (a Georgian national living in Belgium) suffered from late-stage leukemia, tuberculosis and hepatitis type C, a condition requiring complicated, costly treatment [30]. His situation was indeed grave, as during the long procedure the Claimant passed away. Belgian authorities denied him any kind of stay, on the basis of following N. vs the UK standards. Mr. Paposhvili would not face an imminent death upon removal to Georgia, he had a chance of continuing treatment, and had a family to look over him. Literal interpretation of N. standards could have been indeed used to justify expulsion.

However, ECHR decided to reshape those standards in that case. Firstly, it expanded the catalogue of possible outcomes of expulsion which could qualify as inhuman or degrading treatment, specifically to “being exposed to a serious, rapid and irreversible decline in his or her state of health resulting in intense suffering or to a significant reduction in life expectancy” [31]. Subsequently, the court put the burden of proof on public authorities that such situation would occur, thus ordering them to carefully examine the effects of removing a seriously ill individual [32]. Both of those decisions were a breakthrough and finally created a balanced and useful criteria for granting some kind of residence permit based on humanitarian grounds and non-refoulement principle to individuals threatened by the healthcare state in their country of origin. Paposhvili judgment, contrary to the N. verdict, received an applause from NGOs in Europe for making the convention useful for numerous persons in need [33].

Those standards may be applicable in case of theoretical Covid-migrants, however not automatically. Simply arriving from the country damaged by Covid-19 pandemic, even being infected by it, would not meet the criteria to be granted different stay – as numerous bearers of SARS-Cov-2 show none or mild symptoms and safely survive the infection [34]. In order to be given some kind of humanitarian residence permit, two major conditions would have to be met. On the one hand, the applicant would have to be a seriously ill person. It has to be stressed that “seriously ill” does not mean tested positive for Covid-19, but suffering from its dangerous symptoms, or having some kind of coexisting conditions which make him or her more vulnerable to SARS-Cov-2 [35]. On the other hand, expulsion of such individual would have to lead to serious, rapid and irreversible decline in his or her state of health, as explained in Paposhvili judgment. Basically, due to the change in this verdict the practical scope of non-refoulement principle was widened, and could also apply to hypothetical Covid-migrants, who would not qualify for refugee status and subsidiary protection as defined in M’Bodj case.

4. Possible compromise – temporary protection.

Nonetheless, one issue makes it almost impossible to imagine such proceeding being useful in tackling massive influx of persons owing to current time of pandemic. Granting individual protection is a long process, which was especially visible in Paposhvili case, when the Claimant passed away before the court gave its judgment. In such circumstances, one cannot choose standard individual protection instruments as useful measures in tackling SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Issues discussed above leave little hope for immigrants that would try to escape Covid-19 pandemic in their countries of origin. Chances of receiving international protection for them are low, and during the state of emergency their rights may be limited. That being said, keeping masses of persons just across European border, in the middle of current global epidemiological threat, would be a humanitarian catastrophe. Thankfully, European Union is equipped with an instrument useful in such situation – temporary protection.

It was created by the EU in 2001, due to the experiences with mass influx of displaced persons during conflicts after the fall of former Yugoslavia. Idea behind Council Directive 2001/55/EC of 20 July 2001 on minimum standards for giving temporary protection was to manage vast numbers of immigrants efficiently, thanks to special solidarity mechanism between Member States. According to the Directive, Member States have to not only provide financial aid to the ones in need, but also actually accommodate a certain quota of persons [36]. Years before the so called “migration crisis” of 2015, an EU legislation contained a mandatory relocation system. Due to a quite wide definition of “mass influx” used in this act, it can be definitely used in times of global health concern of SARS-CoV-2.

That instrument holds several advantages that could prove useful during hypothetical mass migration owing to Covid-19 pandemic. Firstly, directive purposely shaped temporary protection as a group-based right, contrary to individual right to asylum [37]. This not only allows governments to quicken the procedure, avoiding potential delays (dangerous in times of SARS-CoV-2), but also permits those third country nationals to claim their right to asylum – provided that they are entitled to it. And that is not the only help for those migrants. In fact, aforementioned Directive enumerates several key rights for the immigrants, like access to employment, housing and education [38]. Moreover, temporary protection is limited in time. As a rule, it should only last one year, with possibility of prolonging it by maximum one and a half more [39]. Such condition could make it easier for authorities to communicate mass influx of person to the voters, without causing public outrage. As Kowalski said, this instrument is precisely fit for our times, and could have already been proven useful during the above mentioned “migration crisis” [40].

So, why was temporary protection never tested before? Possibly, due to two vital issues. On the one hand, procedure implementing temporary protection is rather complicated. It requires cooperation between Member States, the Commission and the Council [41], thus leading to a delayed answer. Second reason, according to the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, is a simple change of priorities. The EU throughout the 21st century put pressure on increasing the capabilities of Common European Asylum System, leaving temporary protection forgotten [42].

Having that in mind, it is safe to admit usefulness of this instrument in the times of Covid-19 pandemic. Not only due to reasons listed above. It is perfectly suited for current situation. While today it may seem far away, eventually vaccine would be invented, finally ending the global health concern and thus eliminating the cause of hypothetical mass influx, allowing beneficiaries of temporary protection to return to their homes. Its flexibility combined with fair humanitarian standards could be welcomed by both Europeans and third country nationals, while also securing the world from spread of the new coronavirus. A dream come true from the paradigm of safe migration – “achieving maximum safety for both immigrants and host societies” [43].

5. Conclusions.

Three key issues enumerated in this article do not come close to exhausting all the possible questions concerning theoretical surge of “Covid-migrants”. Nonetheless, one can come to two certain findings. On the one hand, we can be proud of legal instruments developed by the European nations, which may help us endure difficulties of pandemic. On the other – such challenge would require solidarity combined with rationality. Balancing fragile public opinion with moral obligations towards third-country nationals. One could wonder whether nowadays such approach is still possible. In the view of the fact that even if we manage Covid-19 crisis, in those “interesting times” there will be more challenges to come, sooner or later.

###

References:

[1] quoteinvestigator.com/2015/12/18/live/ (access 03.04.2020);

[2] for further reading see J.R. Koo and others, Interventions to mitigate early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore: a modelling study, “The Lancet: Infectious Diseases”, 23 March 2020;

[3] unicef.org/press-releases/covid-19-pandemic-could-devastate-refugee-migrant-and-internally-displaced (access 03.04.2020);

[4] rfi.fr/en/international/20200402-covid-10-is-is-existential-threat-to-our-continent-africa-health-officials-says (access 03.04.2020);

[5] bbc.com/news/world-52114829?intlink_from_url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world/us_and_canada&link_locatio n=live-reporting-story (access 03.04.2020)

[6] france24.com/en/20200313-hungary-s-pm-orban-blames-foreign-students-migration-for-coronavirus-spread (access 03.04.2020)

[7] Statute of the International Court of Justice, article 38, letter b;

[8] un.org/en/ga/sixth/71/resp_of_states.shtml (access 04.04.2020);

[9] International Law Commission, Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, articles 23-25;

[10] ibidem, article 23, point 1;

[11] ibidem;

[12] Nonetheless, using force majeure as a justification is usually not effective for the states, as it implies objective impossibility, not only difficulty, and thus is rarely recognized by courts and tribunals (ed. cars.; for further reading, see International Law Commission, Draft articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, with commentaries, pp. 77-78, paragraph 5);

[13] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, article 4;

[14] European Convention of Human Rights, article 15;

[15] M. Balcerzak, Czy sytuacja związana z koronawirusem uzasadnia notyfikowanie przez Polskę derogacji wykonywania niektórych zobowiązań międzynarodowych z zakresu praw człowieka?, published in przegladpm.blogspot.pl (access 05.04.2020);

[16] ibidem, article 23, point 2, letter b;

[17] ibidem;

[18] Directive 2011/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 on standards for the qualification of third-country nationals or stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection, for a uniform status for refugees or for persons eligible for subsidiary protection, and for the content of the protection granted, art. 2(d);

[19] ibidem, art. 2(f);

[20] ibidem, paragraph 41;

[21[unicef.org/press-releases/interruption-key-water-station-northeast-syria-puts-460000-people-risk-efforts-ramp (access 06.04.2020);

[22] nytimes.com/2020/04/01/world/americas/brazil-bolsonaro-coronavirus.html (access 06.04.2020);

[23] for instance, D. vs the United Kingdom, Pretty vs. the United Kingdom, Aswat vs the United Kingdom;

[24] European Court of Human Rights, judgement from 27 May 2008 in case of N. vs the United Kingdom, application no. 26565/05, paragraph 19;

[25] ibidem, paragraph 17;

[26] ibidem, paragraph 31;

[27] ibidem, paragraph 42;

[28] ibidem, paragraphs 44-45;

[29] M. Kowalski, International Refugee Law and Judicial Dialogue in Central and Eastern Europe, in: A. Wyrozumska (ed.), Transnational Judicial Dialogue in Central and Eastern Europe, Łódź 2017, pp. 392-393;

[30] European Court of Human Rights, judgement from 13 December 2016, in the case Paposhvili vs Belgium, paragraphs 34-53;

[31] ibidem, paragraph 183;

[32] ibidem, paragraph 187;

[33]strasbourgobservers.com/2016/12/15/paposhvili-v-belgium-memorable-grand-chamber-judgment-reshapes-article-3-case-law-on-expulsion-of-seriously-ill-persons/ (access on27.04.2020.)

[34] nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp2009249 (access 27.04.2020)

[35]cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html(access 27.04.2020)

[36] Council Directive 2001/55/EC of 20 July 2001 on minimum standards for giving temporary protection in the event of a mass influx of displaced persons and on measures promoting a balance of efforts between Member States in receiving such persons and bearing the consequences thereof, articles 24-26;

[37] ibidem, article 1 in relation with article 3 point 1;

[38] ibidem, articles 8-16;

[39] ibidem, article 4;

[40] M. Kowalski, From a Different Angle – Poland and the Mediterranean Refugee Crisis, 17“German Law Journal” No. 6 (2016), pp. 978-979;

[41] Council Directive 2001/55/EC of 20 July 2001 on minimum…, article 5;

[42[ H. Beirens, S. Maas, S. Petronella, M. van der Velden, Study on the Temporary Protection Directive. Executive Summary, Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, January 2016, p. 3-4;

[43] A.M. Kosińska, Rola unijnych agencji migracyjnych w kreowaniu standardów zarządzania bezpieczeństwem migracyjnym w dobie europejskiego kryzysu migracyjnego, “Studia Migracyjne – Przegląd Polonijny”, 2019 (XLV), Nr 2 (172), p. 102.